Murakami and Games

Haruki Murakami: “I think video games are closer to fiction than anything else these days.”

Interviewer: “Video games?”

Murakami: “Yes. I don’t like playing video games myself, but I feel the similarity.”

The above fragment comes from the interview literary magazine The Paris Review did with the popular Japanese writer Haruki Murakami. It struck a chord with me.

12 or 13 years ago I somehow started reading Sputnik Sweetheart, or maybe South of the Border, West of the Sun. Someone had recommended Murakami to me, or maybe I read an article. Actually, now I think about it, the first one was South of the Border. I recall choosing it because it was significantly shorter than his other novels in the bookstore. Short novels are a fine way to get to know a writer.

After that I read pretty much all of Murakami’s novels and story collections that’d been translated to Dutch or English.1 My thirst just couldn’t be quenched. Right from the start I was struck by how these books were both exotic and strange, and so very familiar.

Over time my passion waned a bit. Kafka on the Shore was the first book that disappointed. It set up a lot of great stuff, the first part totally had me, but it didn’t really come together in the end. I also started noticing the repetition of themes and motifs between books. But while I got a little less hyped which each successive story, I kept devouring the work. It became a bit of a guilty pleasure, never surprising but always comfortable. And I kept wondering how books by a Japanese man twice my age could feel so close to home.

Then I stumbled upon the above quote, and I thought: of course! It’s games! Long before I read Murakami, I played video games. Especially in the nineties, when they were my favorite hobby, games were very much a Japanese thing. Nintendo games like Mario and Zelda, and more narrative stuff like Final Fantasy,2 lead to my writing about games as a journalist (then writing novels, and finally writing stories for games), and may explain why I understood this writer instantly. The types of characters, worlds, creatures. The tone and humor. I’d seen them all in games.

This doesn’t explain why millions of other westerners fell in love with Murakami too,3 many of whom never played any games. I suppose the short answer is: one way or another, Japanese pop culture became more common in the western world.

So yeah, the quote struck a chord, and I made a note promising myself I’d do something with it someday. Then the Murakami Weekend came along last January, an event with lectures, musical performances and more, celebrating the Dutch release of Killing Commendatore. (Yes, it came out almost a year before the English translation.)

As my last novel was published by Murakami’s Dutch publisher, getting through to the organizers was easy, as was suggesting to them I do a talk about the connection between Haruki Murakami and games. They instantly said yes, which meant there was no way back. I’d now have to do research, talk to people, read stuff, and think things through, to support my claim that there’s more to the similarity Murakami says he feels between games and fiction. (Especially, I’d add, his own work.)

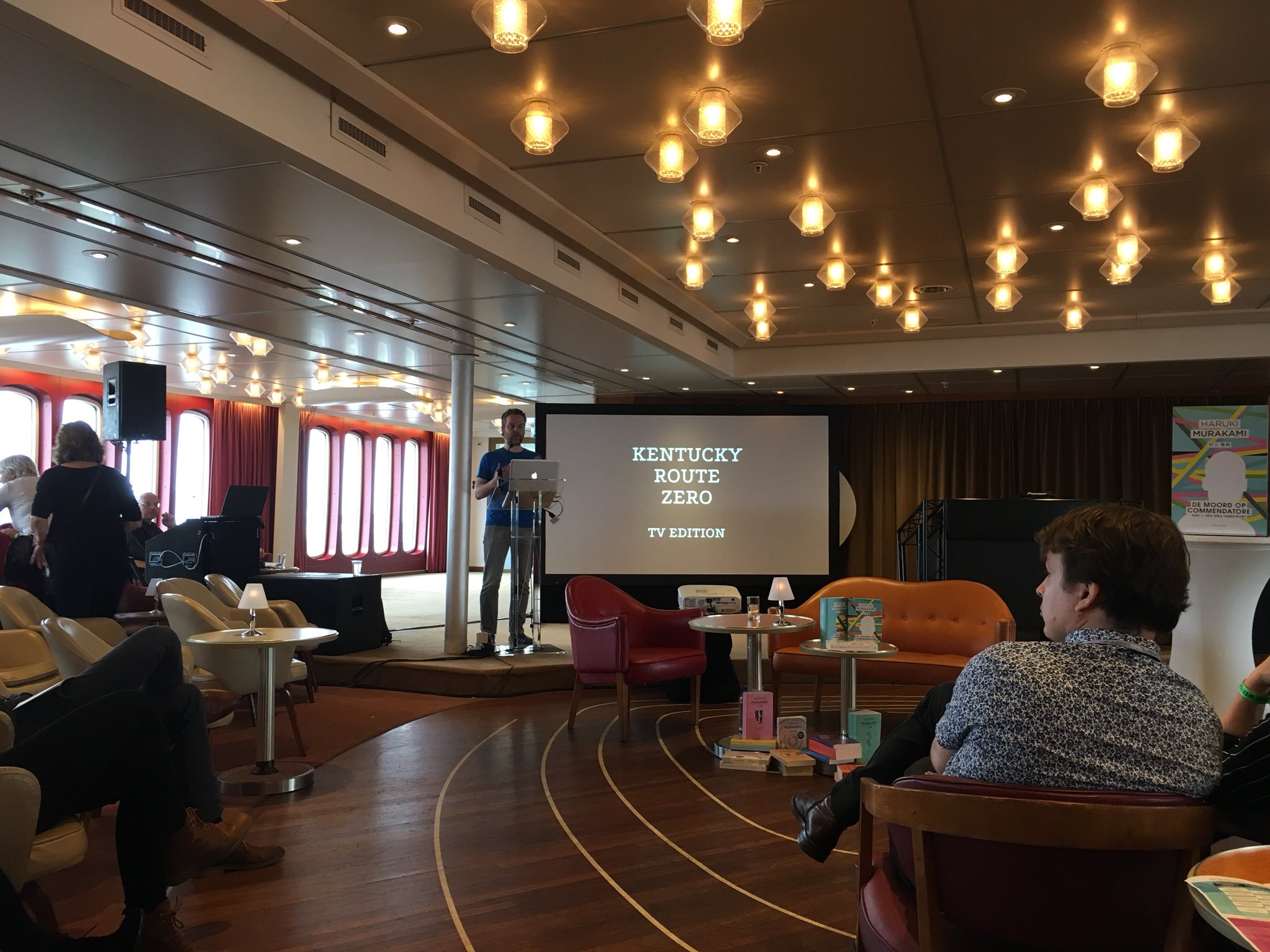

Photo by Sandra Wouters.

So there I was, in a ballroom on a cruise ship in the Rotterdam harbor. It was early on the first day, but there were already quite a few people in attendance. My talk lasted 45 minutes and I had fun all the way through.

Looking back, I think you can call what I did a broad high-level exploration. Which resulted not in a connection, but a bunch of them. I even found a couple of unmistakably Murakami-inspired games, and one that may have inspired Murakami! Reason enough to write it all down here for posterity, and for your enjoyment.

I’ve divided everything into six themes, which I’ll tackle one by one. Oh, and please be cautious: there may be some Killing Commendatore spoilers. Now let’s go!

1. Magic Realism

First, let’s get the obvious out of the way. Magic realism is very common in games, but not so common in (western) literature. Yet Murakami’s particular brand of magic realism, fusing a very normal foundation with a few sprinkles of the weird, is teaching game makers new tricks.

You know what I’m talking about, right? You’re reading a serious story about adults with grown-up problems, and then there are talking cats. Or how about 1Q84’s Little People? In Japanese fiction this is not so strange. Maybe because of Japan’s background of Shinto, the animistic religion in which any natural object (a river, a rock, a shrubbery) can be a god (‘kami’).

You see the cultural descendants of Shinto in Nintendo games and Ghibli movies, among many others. So it’s not the supernatural that typifies Murakami’s work, it’s the way it pops up in otherwise serious narratives, like the giant frog below Tokyo in the After the Quake story collection.

Illustration by Isabella Thermes.

Games almost always feature some kind of mix between the real and the unreal, usually tending towards the latter. I think because of their nature as abstract systems dressed as something recognizable. And by often being a rather similar kind of unreal, games painted themselves into a corner for a long time. They all looked alike and spoke to a largely homogenic group.

Indie game makers have already made big strides here, by drawing from more diverse influences, with Murakami serving as a guiding light for some. A few game makers explicitly say they’re inspired by his writing, while for others it’s an implicit or even subliminal influence.

Take, for example, Cian Rice, who organized a Murakami game jam last year. A game jam is a pressure-cooker type creative challenge, and with this particular jam, the goal was to take something from Murakami’s work and make a small game out of it. Rice told me the following:

Murakami’s habit to combine everyday life with sudden detours inspires me. Mundane things seem more surreal when something strange happens.

That rings very true, and feels like something more game makers should be able to work with!

Another recent example is Memoranda, a Kickstarter-funded game made in Teheran, Iran, about a girl who’s forgetting her own name. The developers were inspired by Murakami, the trailer below even says so. It wasn’t received that well, apparently the puzzles are a little too weird, but it’s an interesting glimpse of what Murakami’s fiction world looks like through the eyes of game makers.

2. Parallel Worlds

Let’s zoom in on one common magical-realistic Murakami element. Even when there are no concrete parallel worlds present, like the highly surreal one in Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World or the more subtle one in 1Q84, there are usually hints of a division between the real and the non-real. The regular and the special.

Killing Commendatore’s main character comments on how he finds it increasingly hard to separate what’s normal and what isn’t. His house on the hill seems to be a special place, with its own special rules. Everything outside it he calls “the normal world”. Other people mostly just pass by. Looking at them from the house, they only seem to have half an existence.

This is similar to the concept of the ‘magic circle’ from game studies. A kind of metaphorical bubble that envelops you and others as you play a game. The game rules create a local, temporary, special reality.

Illustration by Richie Pope.

The well from The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle is probably the most famous example of such a ‘bubble world’ in Murakami’s writing. Commendatore’s hole under the temple is another. So is the wind cave the main character’s sister disappeared in decades ago. When she returned, the main character said it again: “Let’s go back to the real world.”4

Games aren’t just bubble worlds themselves, they often feature parallel worlds too. Take, for example, the Persona games by Atlus. Japanese role-playing games in which the main characters enter parallel worlds shaped by their suppressed subconscious.5 The Persona developers clearly had Murakami on their minds, as they namedrop The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle in the fourth game in the series.6 Although, the author is so famous in Japan, it would be much weirder if no media ever referenced his work.

Guan van Zoggel, a friend and Japan expert, was skeptical of this connection when I asked him about it. He told me that ‘isekai’ (parallel worlds) are so common in Japanese media, it’s become almost a genre by itself. He implied: you should take a closer look at Murakami’s parallel worlds and those in video games, and try to draw more specific parallels. I agree (as does Guan’s wife, he noted), but for this overview it should suffice to say that, yes, there indeed are similarities.7

Illustration by Grant Snider.

3. First-person

Many games are seen from a first-person perspective, and of course many novels are written from the first person. Yet to me Murakami’s books can feel more similar to first-person games than to other first-person novels.

The first-person game perspective became popular because of shooters like Doom and Quake, and you still usually fire guns from this view. That’s a world away from Murakami… Or is it? In 1Q84 Aomame is an assassin, and Ushikawa rents an apartment to wait for Tengo to show up. There even is a word for this in the gaming world: ‘camping’.

Waiting and watching is important in Killing Commendatore too, as the main character’s neighbor, Menshiki, observes his (possible) daughter with binoculars. He does this with such devotion, his whole being is seemingly sucked into his first-person observation. Costing him a lot of energy!

Menshiki’s ritual brings to mind the Hindu concept of the Avatar, where a god descends from the heavens and takes control of a human’s body.8 This concept has been adopted by games (and software), as your representation in a game is called an avatar (as is the picture next to your Twitter account). The ‘Idea’ in Commendatore is clearly an avatar in the Hindu sense. With effort, he spiritually moves from one place to another, ’transfiguring’ from one form to another. And both Menshiki and the Idea have to charge up when they’re done.9

So why do Murakami’s first-person stories feel so gamelike? I think it’s because they’re real-time. I use the phrase as in games terminology: while a movie is tightly edited, so only the most interesting action is shown, many games are played in real-time, with the action flowing naturally. Montage (at moments decided by the game designer, for example) would feel odd and jerky. Which means that sometimes you just walk, or drive, or fly, while nothing happens. Even in a non-arthouse game.

Similarly, in Murakami’s fiction, you often follow what the main character is doing, even if he’s just going through his daily habits, taking a walk or fixing a simple meal. This gives the prose a very specific, rather hypnotic (and game-like) rhythm.

It’s not just the action, the psychology unfolds in real-time too. Especially in the later stories you truly step inside the character’s head, and see what goes on in there. Each change of mental state is observed closely, thorough and honest, with lucid detail. There’s a touch of Asperger too, a certain distance to the world, holding you ever more captive in that first-person view, like Menshiki in his binoculars.

Promotional artwork for the game Mirror’s Edge.

4. Player vs. Programmer

The first quote I jotted down when reading Killing Commendatore was this: “I was simply being dragged along by all kinds of circumstances.” A typical Murakami sentence, I thought, spoken by an artist who accidentally has a career painting commercial portraits. Murakami’s heroes sometimes do want something, but it’s their surroundings that ultimately decide their destiny.

In the Paris Review interview at the top, the author elaborates on this himself:

In my books and stories, women are mediums, in a sense; the function of the medium is to make something happen through herself. It’s a kind of system to be experienced.

So indeed, it’s not the main character, but others, specifically women, who propel the fiction forward. For example, in Commendatore the main character’s wife divorces him, setting the story in motion at the very start.

In Dance Dance Dance Murakami explains what this lack of agency has to do with games. He does this through the voice of the Rat, expressing the idea that he has a meaningless life and never gets anywhere:

I felt like I was in a video game. A surrogate Pac-Man, crunching blindly through a labyrinth of dotted lines. The only certainty was my death.10

Murakami goes even further by comparing his writing process to video games. He does this in the Paris Review interview, but elsewhere too, like in a Dutch interview by Auke Hulst, that was published in newspaper NRC. Here he says:

You know, my brain is rather odd. When I’m writing, I can split it in two. […] I could simultaneously program games and play them too, without me, the player, knowing how I, the programmer, meant the game.11

You could call this empathy: the capacity to imagine what readers will experience when reading your work. But this is a much nicer image: the writer as level designer, creating mazes through which characters (and thus readers) roll like marbles.12

So how is this style of writing reflected in the work? I asked blogger Nate Davis about this, whom I tracked down as he wrote about Murakami and games as early as 2004. He said:

While Murakami’s characters may explore and learn about their environment by themselves, ultimately they wait for a clue for the action that will take them to the next level. They’re looking for the hand of a creator who wants them to advance. And you get the sense that the novel just isn’t going to progress until they work it out.

These characters have a lack of free will, just like game characters waiting for you, the player, to solve a puzzle. Like adventure games,13 a Murakami story is “a system to be experienced”, as he called it himself.

5. Routines

I first noticed this in Killing Commendatore, but it must’ve been in his work for much longer: Murakami is always building routines for his characters, from their simple meals, via sex with married women, to their work processes. In Commendatore he explains his main character’s portrait painting routine in beautiful detail. And we already discussed Menshiki’s routine, observing the girl who might be his daughter.

Routines are so common in the Murakami universe, they’re expected. When a mysterious bell rings at night for a second time, it’s already clear that this is going to happen every night. Couldn’t it just be a coincidence? Nope, of course not!

Talking to Nate Davis again, he mentioned this:

The character in Hard-Boiled Wonderland falls into that alternate simulated world in his own head, where he’s kind-of suspended in an infinite loop of diminishing time intervals that will ultimately destroy his body.

Davis is right. These routines are ‘loops’ that the characters fall into, and ultimately escape, one way or another. Nearly as important as characters building up routines, is that they’re always breaking out of routines too. Even if it’s just to move into new ones.

This reminds me of improvised jazz: the musical performers build up a repeating groove, which they then riff on. Once the routine’s possibilities have been explored and the groove has grown stale, it’s time to transfer into something new.

Photo by Patrick Fraser/Corbis Outline.

It’s easy to see where the routines come from, with an author famous for his routine-heavy life. Murakami wakes up early in the morning to write and exercise, which he talks about extensively in What We Talk About When We Talk About Running.

Now, games are made of routines, ‘systems’, that interact with each other and with you, the player. You grow crops and harvest them. You drop blocks to form disappearing lines. You beat enemies to score money, to buy increasingly powerful weapons, to beat bigger enemies, to earn more money, etc.

In fact, each video game, each software program,14 is a routine at its core: a ‘loop’ that runs from player input to audiovisual output. The program checks whether you’re pressing a button, processes that, changing values in its memory, and shows you the results. This loop is processed dozens of times per second.

Menshiki seems to refer to the dynamic values of software when he talks about the “information world” in which he works, where you can “lose some and win some”. The calculator in Hard-Boiled Wonderland, juggling numbers among his two brain halves, is another externalized example of this returning motif.

6. Art for Everyone

This is another theme I hadn’t noticed in Murakami’s work before Killing Commendatore, I think because it wasn’t in there. But this time, it’s front and center. Does the main character follow his artistic urges, or does he give people what they want? Or can these two things somehow be combined?

While this discussion might be new in his fiction, it’s always been present in the discussion about it. Is it literature with an uppercase or a lowercase L?

In all literature, and all art, there’s a friction between complex, difficult work that the creator makes for herself (without caring about the audience) and accessible work meant for the widest possible audience (without caring about any kind of ‘internal need’ on the creator’s end). But with Murakami this friction is amplified. It’s Nobel Prize worthy literature with deep and important themes, that anyone can understand.

All of this reminds me of games, although the starting point is pretty much the opposite. A game is clearly a working and understandable product first (as it has to function as expected, and is often sold as a commodity), and art second. Since the rise of indie games the latter has grown in importance, but mostly games are still seen through the lens of the user, like industrial design.

Like with magic realism, Murakami could give game makers some guidance for a different position on the spectrum of art and product. And also like magic realism, there are already some good examples. Most importantly Kentucky Route Zero, one of my favorite games of recent years. It’s not a Murakami game in the literal sense, but sure feels like one of his books. Much more than the aforementioned Memoranda, to be honest.15

Anyway. Murakami’s accessibility is a very conscious effort on the author’s side. He apparently once said that in his native country, 1 out of 10 people should be able to understand him. Which sounds humble at first, until you realize Japan has about 125 million inhabitants.16

So he writes short, clear, literal sentences, with real-time patience so there are no jarring jumps to decipher. He doesn’t eschew copy writing tricks: the prose is ‘actionable’, and there’s foreshadowing and cliffhanging all over the place.

Where does all this come from? Well, I was intrigued to find that the young Murakami was acquainted with Shigesato Itoi. The Japanese ad man famous for his talk show appearances and daily haiku-like blog, who provided the voice of the father in My Neighbor Totoro and, yes, came up with the ‘Game Boy’ brand name.

Here’s the kicker, though: Shigesato Itoi is the maker of Mother, a series of role-playing games that achieved cult status in the nineties. Mother 2 was released in English, as Earthbound, but only in the USA.17 It plays like a Murakami story, with a normal world where strange things take place. In the trailer below the characters even descend into a well!

Murakami and Itoi don’t just know each other, they worked together. Itoi invited the writer to produce short stories for brands, and they even published a story collection together, Yume de Aimashou (‘Let’s Meet in a Dream’) in 1981. It was never released in English, but there’s a fan translation online.18 According to one rumor, Earthbound hides one of the Yume de Aimashou stories, but this is false. There are similar bits of writing in there though.

Did Itoi and his games influence Murakami? That’s hard to say, but I’m pretty sure the both of them were thinking about some of the same things when they were creating their art.

In the world of games, Earthbound made a lasting impression for sure. It inspired recent games like Undertale and Omori. The makers of YIIK, which comes out soon, say they were inspired by both Earthbound and Murakami, tying all of this together neatly.19

Finally

I want to close off with the quote I started with:

Haruki Murakami: “I think video games are closer to fiction than anything else these days.”

Interviewer: “Video games?”

Murakami: “Yes. I don’t like playing video games myself, but I feel the similarity.”

Murakami’s first remark is actually a bit longer:

So fiction itself has changed drastically—we have to grab people by the neck and pull them in. Contemporary fiction writers are using the techniques of other fields—jazz, video games, everything. I think video games are closer to fiction than anything else these days.

If you ask me, all media forms are close. Have always been close. It’s just that digitalism has made it more obvious. As such, they all inform each other, ultimately helping them toward the goals of (on one hand) giving the creator’s subconscious a voice and (on the other) giving you a great experience. Which doesn’t mean it’s a bad idea to take a closer look at some of their similarities!

That’s it! If you have something to add, or if you caught untruths, shout out. I look forward to further hybrid writing explorations, so keep me updated if you’re working on anything. Finally, feel free to share this article with your friends. I want this to be useful for as many people as possible. While preserving what I set out to say!

- In those years, not all of the earlier work had been translated to Dutch, but some had been translated to English (and vice versa). I was basically waiting for the translators to finish their jobs. ↩

- Games got me into Japanese animation too. I regard Nintendo’s Shigeru Miyamoto, Studio Ghibli’s Hayao Miyazaki and Murakami as a holy trinity of older Japanese men whose family name starts with an M, and who have helped shape my cultural sensibilities. ↩

- I remember one time at a local bookstore, maybe a year after I discovered Murakami. It was a Saturday, a busy day to begin with, but around the ‘M’ shelf there was an incredible throng of people all trying to lay their hands on the particular oeuvre-completing book they didn’t yet own. I was a little annoyed that the author apparently no longer was my author. ↩

- I’m reading Killing Commendatore in Dutch, and I’m citing from memory here, so this is likely not a literal quote. By the way, the book was released in two parts here, and for my talk I read the first. The second was released a month later, and as of this writing I have yet to finish it. I heard a rumor that there’s a more literal parallel world in this book after all. Who knows! ↩

- For example, when they visit the mind of someone who regards other people mainly as ways to make money, everyone walks around as ATM machines. ↩

- This takes place in a literature class within Persona 4. It’s not a very deep or meaningful reference, but if you’re curious, here’s a transcript of this part of the game. ↩

- Surely scholars will discuss Murakami’s parallel worlds for decades to come. In a recent email interview with Arjan Peters in the Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant, Murakami gave the following explanation: “If you look at it from a certain angle, our daily life may look ordinary, boring and extremely continuous. But from a different angle, it’s full of amazing contradictions, cracks and irrationality. And regularly we are overwhelmed at night by incomprehensible dreams. Inside us, things are constantly bubbling up that are immeasurable with existing standards, that we can not serve out with existing mugs or bowls. We simultaneously live in those two worlds; that’s what I feel it comes down to. The role of fiction is – in my opinion – to focus the spotlight on that ‘other angle’ and magnify it. If possible with a positive attitude.” ↩

- In Shinto there’s no avatar concept, I think, if only because there’s no concept of a divine parallel world. Kami simply live among us. However, they can and do take the form of humans. ↩

- Using energy and then having to recharge sounds like a rather game-like thing by itself. ↩

- That’s a direct quote, as I read this book in English. ↩

- Ben Dooley wrote about a 2008 public interview in which Murakami gave another version of the same idea: “Writing a story for me is just like playing a video game. I start with a word or idea, then I stick out my hand to catch what’s coming next. I’m a player, and at the same time, I’m a programmer. It’s kind of like playing chess by yourself. When you’re the white player, you don’t think about the black player. It’s possible, but it’s hard. It’s kind of schizophrenic.” ↩

- There’s a snarkier reading too. Like Stephen King, Murakami is one of those writers who don’t carefully plan out their novels before they start writing. So he literally doesn’t know where the story is going. This gives the longer books something of an ‘episodic’ quality, like a serial story or a level-based game, and causes some of my recent disappointment, I think. Unlike with King, the books never end in a big explosion though, which I appreciate. ↩

- Also like detective stories. Sherlock Holmes stumbles upon a chaotic situation that he proceeds to unravel, tidying up reality, one piece of evidence at a time. Murakami’s book often unabashedly are detective stories! ↩

- I like to think of games as software with only intrinsic goals. ↩

- It’s recognizable as an adventure game, but made with such artistry and deep undercurrents that I can totally see it as Nobel Prize winning literature. Unsurprisingly, it’s not made by typical game developers, as the makers come from the Chicago art scene. So far, four Kentucky Route Zero episodes have appeared as download games, and this year the full five-part series will be released on disc, as the ‘TV Edition’. ↩

- In the email interview with De Volkskrant, discussed in footnote 7, Murakami talks about finding access to things in the subconscious, retrieving them and shaping them as an artist. He says: “That form should not be complacent, but should enable an intimate and powerful bond with the audience (the reader). At least, with that idea I write fiction.” ↩

- As far as I know, Earthbound is the only game to ever be sold with ‘scratch and sniff’ cards that you had to smell at certain points. I’m catching a sensory Murakami whiff here! After a few digital releases, Earthbound was sold in European physical stores in Europe for the first time last year, as part of the SNES Mini. Unfortunately, this mini game console with 20 built-in games sold out quickly and is already hard to come by. Well, it doesn’t include the smell cards anyway. ↩

- Like Murakami’s early work that was translated, the collection seems to be closer to Itoi’s blog than Murakami’s present day patient lucidity. ↩

- The makers of YIIK call it a “postmodern” RPG, a label often smacked upon Murakami, usually just meaning ‘surreal, disjointed and weird’. Yet Murakami’s work has little of the multiple-truths confusion that I think is essential to postmodernism. The games medium is far more postmodern! Game critic Tim Rogers was actually one of the first to write about Murakami and games, inspiring Nate Davis and myself, and hangs it on postmodernism big-time. Judge for yourself. ↩